1. The Hidden Gap Between Contracts and Code

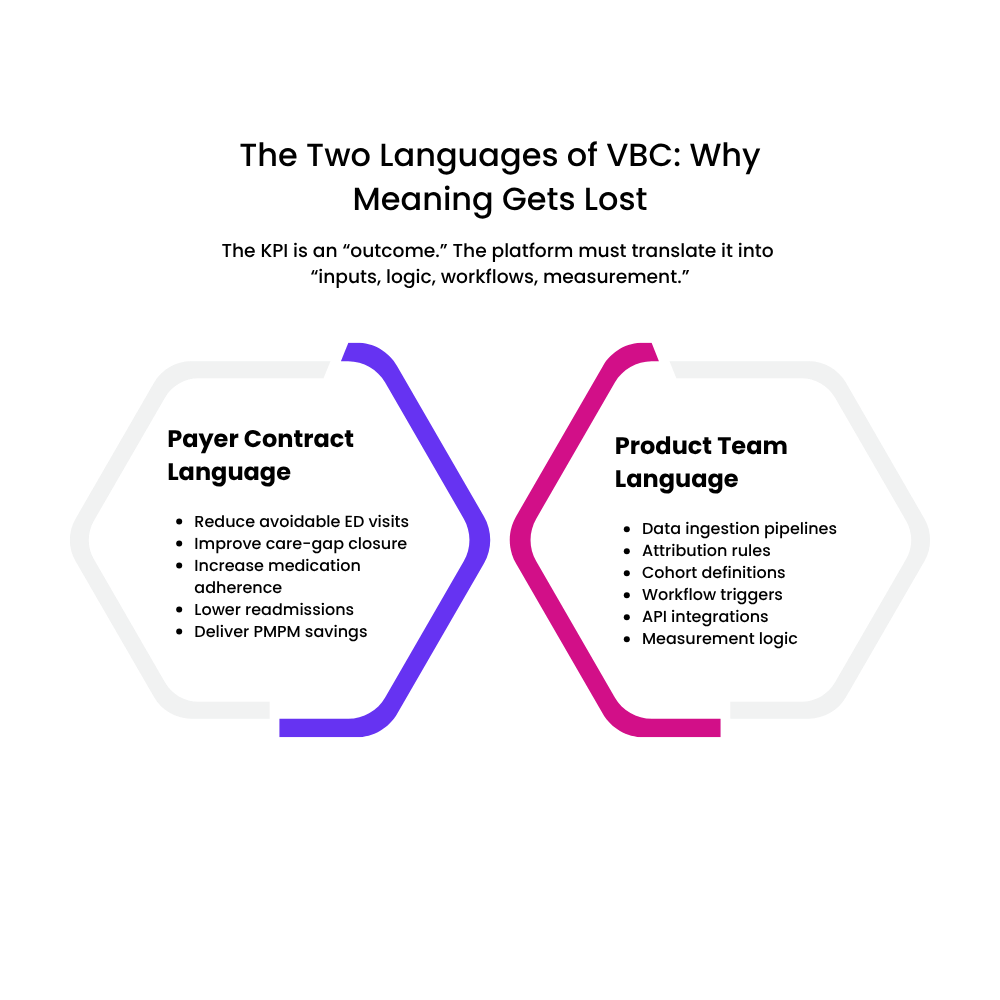

For most VBC startup founders, the toughest moment doesn’t come while pitching to a payer; it comes after signing the contract. That’s when the realization hits: the KPIs inside the agreement sound logical on paper, but translating them into an actual product roadmap is far more complex. Payer contracts speak the language of readmission reduction, care-gap closure, RAF uplift, PMPM savings, utilization shifts, chronic-condition control, and risk attribution. Product teams, on the other hand, think in features, events, workflows, data schemas, integrations, and APIs.

Somewhere between these two worlds, critical meaning gets lost.

Most founders underestimate just how different these vocabularies really are. A metric like “reduce avoidable ED visits by 8%” might look like a simple north star; in practice, it requires claims ingestion, utilization categorization, attribution logic, lag-aware analytics, and near-real-time care navigation triggers. A target like “improve care-gap closure by 15%” demands a full pipeline of HEDIS logic, member eligibility reconciliation, provider alignment, evidence-of-compliance documentation, and longitudinal measurement.

This mismatch is not unique. Industry research repeatedly shows that payer expectations and startup capabilities often move in parallel but rarely intersect. A Deloitte review of VBC innovation notes that while payers emphasize quality, risk, and ROI, startups emphasize features and workflows, creating persistent misalignment until both sides share a common operational vocabulary (Deloitte Insights, Value-Based Care Innovation Study).

For founders, this is where early momentum often stalls: the contract promises outcomes, but the product is not yet engineered to measure or influence those outcomes. And unless this gap is closed quickly, even the strongest payer relationships can lose confidence.

This section sets up the central tension of your blog- the gap isn’t about effort or intent; it’s about translation. The rest of the piece will show founders how to bridge it with clarity, strategy, and a shared language of value.

2. Why This Gap Exists in the First Place

Payers write contracts. Engineers build products. And they speak different dialects.

Value-based care contracts are negotiated by actuarial teams, medical directors, utilization managers, and network strategy leaders; people who think in terms of cost curves, quality thresholds, risk pools, and financial levers. Their KPIs are shaped by CMS standards, HEDIS benchmarks, RAF scoring policies, and decades of claims trend analysis.

Startups, however, are built by product managers, engineers, and data teams who think in objects, schemas, APIs, life-cycle events, and user flows. Their instinct is to design features, not financial levers.

This is where the misalignment begins:

- The payer side thinks in outcomes and economics.

- The founder side thinks in functionality and workflows.

Without a translation layer in between, both sides believe they’re talking about the same thing — when in reality, they aren’t.

KPIs are written in clinical and actuarial logic, not product language.

Contracts reference performance targets in ways that feel deceptively straightforward:

- Reduce readmission rates by 10%

- Increase care-gap closure for diabetic members

- Improve medication adherence for high-risk cohorts

- Lower avoidable ED utilization

But none of these are feature statements.

They are data + workflow + attribution + measurement statements, spread across multiple teams, datasets, and time horizons.

A McKinsey analysis of VBC models notes that more than 60% of failed payer-startup partnerships collapse because the tech platform cannot operationalize the KPIs in the contract (McKinsey, “Unlocking Value-Based Care at Scale”). This gap is systemic, not accidental.

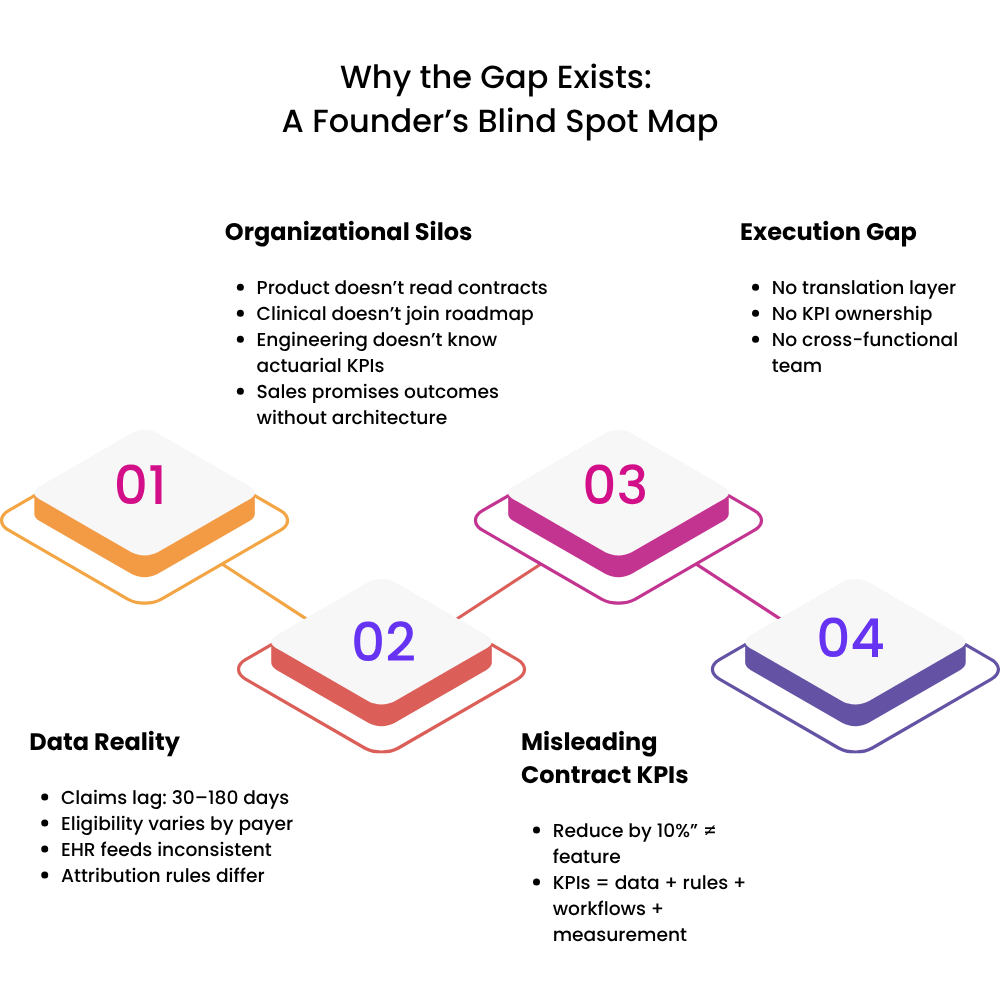

The data required to achieve KPIs is not available on Day 1.

Founders often forget that most VBC KPIs depend on:

- Claims data (with 30–90 days lag)

- Eligibility files (with inconsistent formats)

- Clinical feeds (varies by EHR vendor maturity)

- Attribution logic (defined differently across payers)

- Quality measure definitions (updated annually)

The contract may reference targets within six months, but the data infrastructure to support them may take nine months if not planned early.

Organizational structure worsens the gap

Inside many early-stage VBC startups:

- Product teams rarely read payer contracts.

- Clinical leaders rarely sit in product roadmap discussions.

- Engineering teams rarely understand actuarial KPIs.

- Sales teams rarely understand how features support quality measures.

Without cross-functional translation, even brilliant teams build in silos.

Harvard Business Review notes that cross-functional breakdown is the #1 cause of failed health-tech pilots, particularly in data-heavy sectors like VBC (HBR, “Why Health Tech Fails to Scale”).

Founders assume KPIs will “map themselves”; they never do.

Most founders believe that if they build a great platform and ingest enough data, the KPIs will fall into place naturally.

In reality:

- KPIs must be translated into data models.

- Data models must drive workflows.

- Workflows must drive behavior change

- Behavior change must drive measurable outcomes.

This chain must be intentionally engineered — it never emerges organically.

In short:

The gap exists because VBC KPIs are financial and clinical commitments, while early-stage products are functional and operational tools. Bridging them requires a common language, and a deeply intentional product strategy.

3. How Contract KPIs Translate (or Don’t Translate) Into Data Logic

KPIs look simple on paper, but underneath each one sits an entire data engine.

Most payer contracts express KPIs as clean, outcome-oriented goals:

- Reduce 30-day readmissions

- Improve diabetic care-gap closure

- Lower avoidable ED utilization

- Increase medication adherence in high-risk cohorts

To a founder, this reads like a direction.

To a product team, it should read like a blueprint for an entire data ecosystem.

But most early-stage VBC startups only discover this after signing the contract; when it’s time to “operationalize” the KPI and the gaps become obvious.

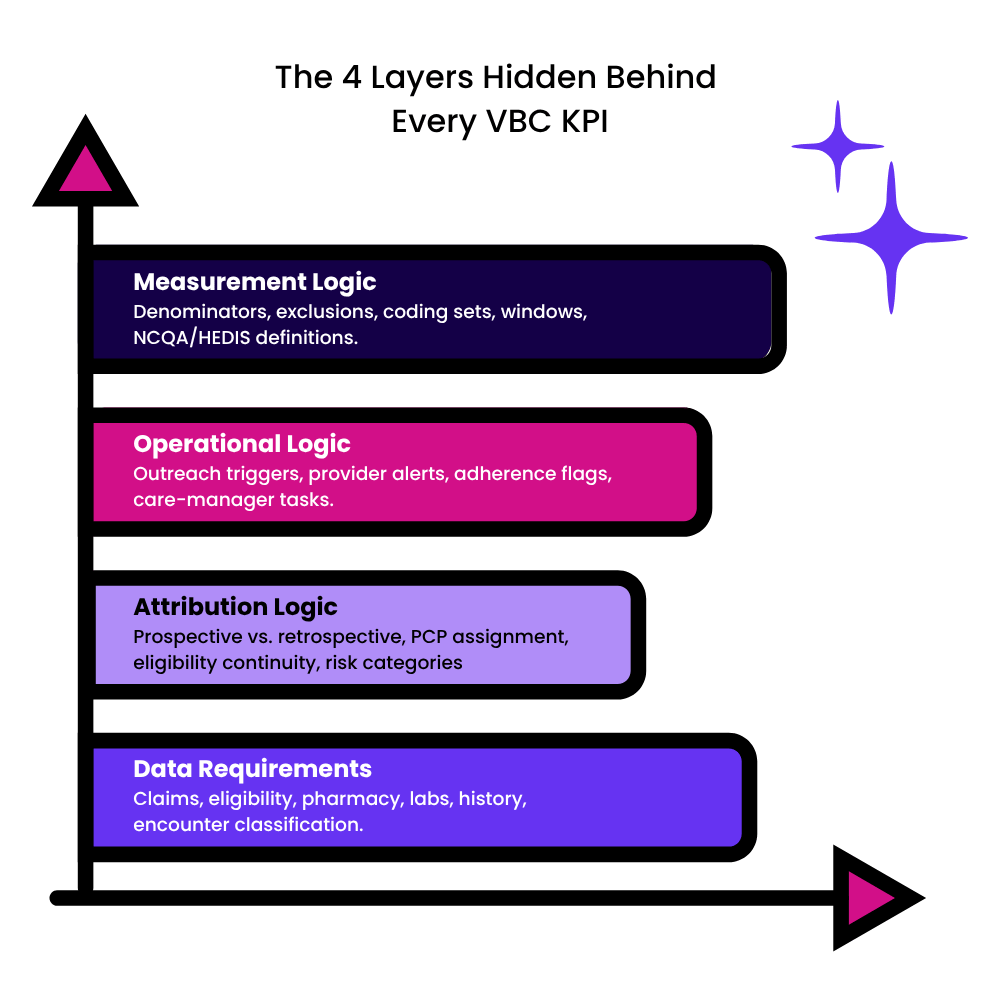

Every KPI breaks into four layers of product reality

To translate contract language into actual product architecture, each KPI must be decomposed into the following logical layers:

A. Data Requirements (What must we ingest?)

Example: Reduce avoidable ED visits

This requires:

- Claims (facility, professional, pharmacy)

- Member eligibility files

- ED encounter categorization (NYU ED algorithm etc.)

- Prior 12–24 months utilization history

Most startups only ingest a subset, making the KPI impossible to measure accurately.

B. Attribution Logic (Whose outcome is “ours”?)

Payers use attribution to determine which members “belong” to your program or platform.

For example:

- Prospective vs. retrospective attribution

- PCP assignment logic

- Continuous eligibility rules

- Risk adjustment categories

Misinterpreting attribution can distort KPI measurement by 20–40%, according to NCQA’s analysis of HEDIS measurement variance.

C. Operational Logic (What user action or workflow changes this KPI?)

Example: Improve medication adherence

Your product needs:

- Daily/weekly adherence flags

- Care manager outreach tasks

- Behavioral nudges

- Provider alerts

- Root-cause capture (cost, access, confusion, polypharmacy)

Without these workflows, the metric sits untouched; your platform “measures” adherence but has no way to influence it.

D. Measurement Logic (How do we calculate improvement?)

Every KPI has a formula buried behind it.

Example: Care-gap closure is never just “who got the exam.”

It includes:

- Eligible denominator logic

- Timing windows

- Clinical exclusions

- Codes considered compliant

- Member roll-on/roll-off effects

- HEDIS annual updates

A change in denominator definition alone can alter performance by double digits, according to NCQA’s measure-change audits.

The dangerous assumption: “If we ingest the data, we can measure the KPI.”

No, you can’t; not without:

- Normalization

- Coding harmonization

- Deduplication

- Longitudinal stitching

- Timeliness handling

- Lag-sensitive calculations

- Cohort persistence rules

This is why one payer’s readmission rate and your platform’s readmission rate rarely match; they’re using different logic, not different results.

It is found in a number of studies that data definition mismatches are the #1 cause of payer–startup disputes during quarterly performance reviews.

Why translation fails: the founder lens vs. the contract lens

- Founders see KPI → feature

- Payers see KPI → economics

- Clinicians see KPI → outcomes

- Engineers see KPI → logic

- Data teams see KPI → models

Unless these lenses are aligned early, founders end up building features that look good in demos but don’t meaningfully move contractual outcomes.

The result? Product teams chase KPIs retroactively.

Instead of building proactively with contract language in mind, many startups enter a cycle of:

- Verifying KPI definitions months after launch

- Rebuilding data pipelines

- Re-scoping workflows

- Recomputing baselines

- Explaining discrepancies to payers

- Losing trust in QBRs

This is the cycle that kills many early VBC partnerships.

4. The Technical Barriers Nobody Anticipates

I. Claims data isn’t “data”- it’s a messy, lagged, multi-format beast.

Founders often assume claims data arrives neatly packaged. In reality:

- Claims lag ranges from 30 to 180 days depending on payer workflows.

- Facility vs. professional claims often arrive separately.

- Pharmacy claims follow different pipelines altogether.

- Diagnosis codes change annually (ICD).

- CPT/HCPCS definitions change quarterly.

A Milliman actuarial brief notes that claims inconsistency alone can shift cost or utilization metrics by up to 12–15% between reporting periods.

You can’t operationalize KPIs like ED visit reduction or readmission rates without decoding this maze.

II. Identity resolution is harder than building an entire MVP.

To measure anything longitudinally, you must know who the patient is across:

- Claims feeds

- EMR feeds

- Lab data

- Pharmacy data

- Care management notes

- SDoH sources

- HIE or ADT feeds

- Provider rosters

The problem?

Names, ages, addresses, IDs, and insurance details rarely match.

Identity resolution models (probabilistic + deterministic matching) are essential, but most VBC startups underestimate this and end up with fragmented member timelines, which destroy KPI accuracy.

CMS has repeatedly emphasized member matching as one of the biggest barriers to successful interoperability (CMS/ONC Joint Interoperability Report).

III. Attribution logic is not just hard- it is inconsistent across payers.

Different payers use:

- Prospective vs. retrospective attribution

- HMO contract logic vs. PPO logic

- Continuous eligibility rules

- PCP assignment methods

- Varying lookback periods

- Different “break in coverage” tolerance

A founder might assume a patient “belongs” to their program…

…but the payer’s attribution system might drop that member for missing a single eligibility file update.

If attribution isn’t implemented exactly as the payer defines it, your KPIs will never match theirs, creating immediate mistrust.

IV. KPI measurement requires longitudinal stitching, not one-time analytics.

Metrics like:

- Readmission rate

- Care-gap closure

- Diabetic control

- Medication adherence

- Total cost of care

- Risk-score impact

- Preventive utilization

All depend on timelines, lookback windows, rolling cohorts, and continuous tracking.

Founders often build dashboards, not longitudinal engines.

It has been consistent with most studies that most VBC startups overestimate their ability to measure time-based outcomes by 2–3x because they lack longitudinal architecture.

V. Normalizing medical, behavioral, pharmacy, and SDoH data is a full-time job.

To evaluate VBC KPIs, your system must combine:

- ICD + CPT/HCPCS codes

- LOINC + lab results

- NDC pharmacy data

- SDoH indicators

- Provider directories

- Clinical exclusions

- CMS quality measure logic (HEDIS/eCQM)

- ADT event codes

Each domain uses its own standards and update cycles.

Without normalization:

- Member timelines break

- Utilization categories fail

- Quality measures miscalculate

- Risk models drift

- Payer reconciliation doesn’t match

This is where founders hit the wall; you can’t fix outcomes if your inputs aren’t standardized.

VI. EHR interoperability is not “FHIR-ready” in the real world.

Many VBC founders assume FHIR will magically solve everything.

Reality check:

- Most EMR vendors only expose limited FHIR resources.

- Bulk FHIR (Flat FHIR) adoption is still low.

- Some small EMRs still rely on CCD/C-CDA export or HL7 v2 feeds.

- FHIR implementations differ by vendor — even for the same resource type.

ONC’s 2024 Interoperability report states that FHIR consistency across vendors remains one of the biggest blockers to scalable data exchange.

VII. Payer KPIs rely on data the founder does not control.

Many KPIs reference outcomes tied to providers, PCPs, specialists, health systems, pharmacy networks, care managers, and even patient behavior.

Meaning:

Your product can influence these outcomes, but it can’t own them.

This is why translating KPIs directly into product features often fails. You must build influence loops, not control loops.

The Reality Check for Founders

Most VBC startups aren’t “failing.”

They are simply bumping into the complexity of the healthcare system for the first time.

The barriers are not technical bugs; they are systemic truths of healthcare data and economics.

And now that founders understand these hidden landmines, the next section will show what happens when product and contract drift apart in real life.

5. Real-World Consequences When Product and Contract Drift Apart

A. Quarterly Business Reviews (QBRs) turn into damage-control meetings.

The first sign of trouble is usually the QBR.

-Your platform reports a 14% improvement in care-gap closure.

-The payer’s internal analytics show 6%.

Neither number is “wrong.”

-They are simply calculated using different attribution rules, different denominators, different eligibility windows, and different clinical exclusions.

But in the payer’s eyes?

-It signals unreliability, the most dangerous reputation a VBC startup can earn.

A AHIP payer survey reported that “data inconsistency is the top reason early-stage VBC vendors are not renewed.”

B. Payers lose confidence and slow down expansion, renewals, and contract activation.

When KPIs don’t match or when product features don’t influence contractual outcomes, payers become cautious:

- Expansion pauses

- Renewals are postponed

- Additional cohorts aren’t assigned

- Budgets are rerouted to other pilots

- Internal champions lose political capital

Momentum, the oxygen of early-stage VBC startups, evaporates.

C. Product teams get trapped in a cycle of retroactive fixes.

Instead of building a scalable roadmap, teams scramble to:

- Reverse-engineer payer logic months after launch

- Rebuild cohorting engines

- Patch attribution mismatches

- Rewrite quality measure code

- Reprocess months of claims

- Fix dashboards that “don’t match the payer’s”

This “reactive mode” creates technical debt that can take 6–12 months to unwind.

Mathematica notes that VBC vendors who operate in reactive mode lose 30–40% of engineering productivity to rework.

D. Front-line users stop trusting the platform.

Care managers, providers, and clinical-ops teams rely on trustworthy signals. If alerts, gaps, risk flags, or timelines keep shifting as bugs get fixed:

- Care teams revert to spreadsheets

- Providers stop logging interventions

- Outreach becomes inconsistent

- Engagement collapses

- Outcomes stagnate

Without user trust, even the most elegant platform becomes “yet another tool we don’t use.”

E. The financial model starts breaking down.

When KPIs fall short, two things happen:

- Shared-savings payouts shrink (or disappear).

- Performance guarantees in the contract become liabilities.

Some VBC contracts include:

- Performance clawbacks

- Minimum outcome thresholds

- PMPM reductions

- Value-adjustment clauses

A mismatch between product capability and contract KPIs can convert a promising partnership into a financial burden.

F. The payer-startup relationship becomes strained.

When contract-language and feature-roadmap diverge, the relationship suffers:

- The payer questions the startup’s maturity.

- The startup feels the payer is “moving the goalposts.”

- Roadmap discussions turn adversarial.

- The “innovation-friendly” sponsor inside the payer loses internal support.

A ZS Insights analysis on payer-vendor partnerships found that trust erosion is the #1 predictor of pilot failure in VBC collaborations.

G. Worst-case: The startup gets labeled as “not enterprise ready.”

This label spreads quickly inside payer ecosystems.

It can quietly shut the door to:

- Other local or national payers

- Provider-sponsored plans

- ACOs, MSOs, and CINs

- Population-health networks

- State Medicaid pilots

- Employer groups

And this often happens not because the product is bad-

–but because the product wasn’t aligned with the contract from Day 1.

The Biggest Consequence? Lost Time.

A misaligned product-contract pairing can cost a startup:

- 12–18 months of runway

- 2–3 engineering cycles

- A promising payer relationship

- Momentum in fundraising

- Internal morale

- Market credibility

This is why translating KPIs into product logic isn’t just tactical —

-it’s existential.

6. What VBC Founders Can Do Differently (Actionable Strategy)

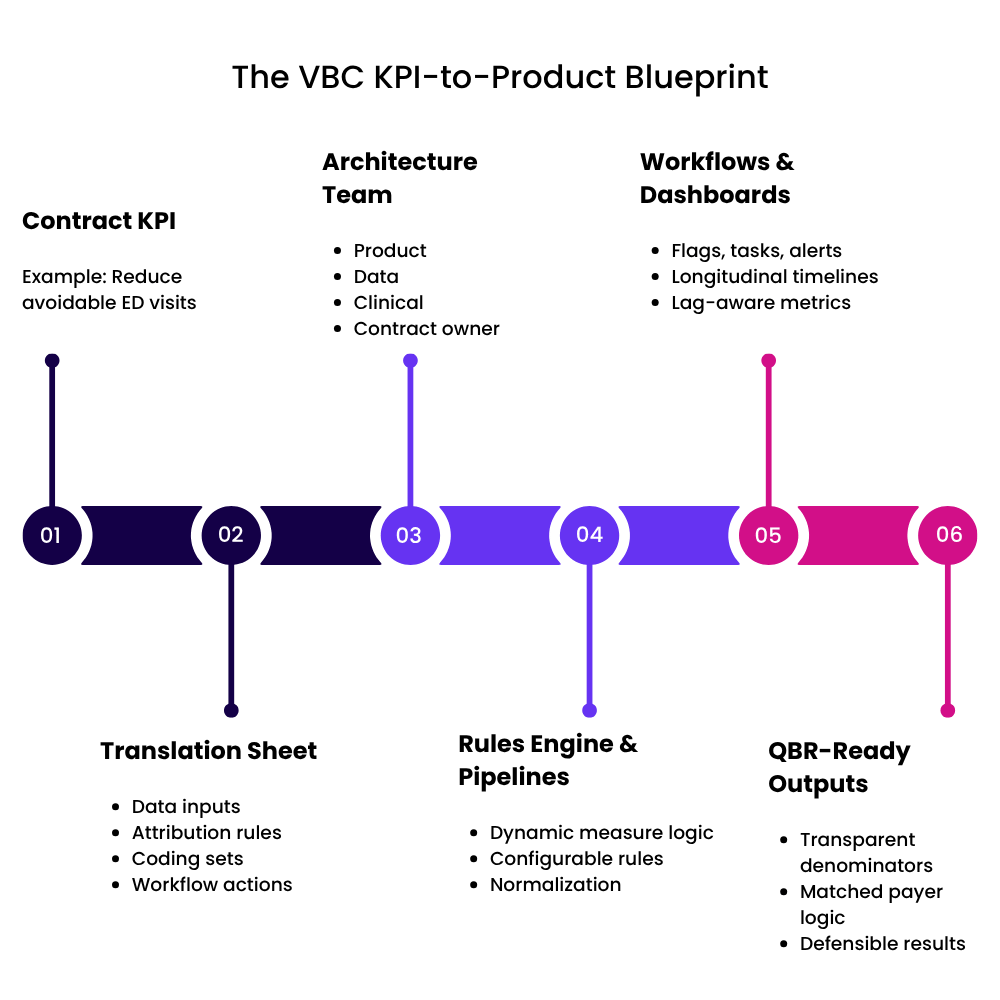

I. Treat payer contracts as product requirements, not legal documents.

Most founders read payer contracts like business agreements.

Instead, read them like product specifications.

Every KPI in the contract should lead to a structured mapping:

KPI → Data Inputs → Attribution Rules → Workflows → Measurement Logic → Features

For example:

“Reduce avoidable ED visits” should instantly translate into:

- ED categorization engine

- Claims pipeline with lag handling

- Cohort attribution rules

- Outreach triggers for high-utilizers

- Baseline calculation + monitoring dashboard

This mapping prevents mismatches later and aligns every team on what the product must actually do.

II. Build a “KPI Translation Sheet” before building any feature.

A KPI Translation Sheet acts as the master document connecting:

- Payer KPIs

- Technical definitions

- Data sources

- Clinical rules

- Required workflows

- Expected behaviors

- Reporting formulas

This creates one source of truth, and avoids the common scenario where engineering, clinical ops, and payer teams each interpret KPIs differently.

Think of it as your Rosetta Stone between contracts and code.

III. Create a KPI Architecture Team early, even if small.

This cross-functional “micro-team” should include:

- 1 product manager

- 1 data engineer or analytics lead

- 1 clinical SME

- 1 business/contract owner

Their job:

– Translate KPIs → architecture → workflows → dashboards.

– If you wait to form this team until after contract signature, it’s already too late.

Platforms like Aledade, Signify Health, and Oak Street Health have explicitly credited cross-functional KPI teams as the foundation of their VBC success (public earnings calls + VBC governance reports).

IV. Build flexible rules engines, not hardcoded KPI logic.

-KPIs change.

-HEDIS updates.

-Quality measures evolve.

-Attribution rules shift.

-Eligibility formats vary by payer.

Hardcoding logic means you’ll break every time something upstream changes.

Instead:

- Build condition-based engines

- Allow dynamic configuration of coding sets

- Externalize measure definitions

- Parameterize attribution logic

Your system should be able to adjust to:

“Diabetic Eye Exam” changing its measurement window

– without needing a 4-week engineering sprint.

V. Align product sprints with contract timelines.

You can reverse-engineer this backward:

- If Q2 has the first performance review,

- And you need 3 months of data,

- And ingestion + normalization takes 60–90 days,

- And onboarding the payer takes 30–45 days…

Then KPI-enabling features must be built before contract launch.

Many VBC startups fail because their “feature readiness” lags behind “contract obligations” by one or two quarters.

VI. Put clinical and actuarial voices inside product planning.

Clinical SMEs help ensure:

- Quality measures are interpreted correctly

- Coding logic is accurate

- Exclusions are applied properly

- Workflows reflect real clinical practice

Actuarial or payer operations voices help ensure:

- The product influences cost trends, not just user experience

- KPIs are interpreted exactly as payers calculate them

- Shared-savings models are reflected in reporting

This prevents the product team from building “nice features” instead of “contract-critical features.”

VII. Build a KPI Simulation Environment (very few startups do this).

Before going live with a payer, simulate:

- Attribution outcomes

- Eligibility roll-on/roll-off

- Readmission rates

- ED visit counts

- Quality measure calculations

- Claims lag effects

- Risk-score changes

A KPI simulation environment reveals mismatches before the QBR does.

It’s the equivalent of unit testing for your entire VBC business model.

VIII. Co-design your roadmap with the payer wherever possible.

Payers love vendors who bring them closer to their own goals.

Invite them into:

- KPI interpretation sessions

- Data definitions

- Baseline calculations

- Workflow mockups

- Dashboard prototypes

This builds alignment, trust, and early buy-in.

It also ensures your product features directly influence the metrics the payer cares about.

IX. Document your “KPI Measurement Policy” and share it openly.

This should include:

- Definitions

- Denominators

- Exclusions

- Attribution logic

- Lookback windows

- Lag rules

- Data sources

- Alignment notes with NCQA/HEDIS/CMS

Transparency builds credibility.

Credibility builds renewals.

Renewals build your VBC business.

X. Build your product as if the QBR is tomorrow.

If every founder asked:

“Could I defend these metrics to a payer tomorrow?”

-they would prioritize very differently.

This lens forces:

- Operational realism

- KPI alignment

- Engineering discipline

- Clinical grounding

- Better cohorting

- Better workflows

- Better measurement

VBC is unforgiving, but founders who align contract → logic → workflow → feature earn payer trust faster than competitors.

7. Conclusion: Building Products That Actually Deliver on VBC Promises

This is where great VBC products are truly built: at the intersection of contracts and code.

In value-based care, success doesn’t come from having the smartest model, the cleanest UI, or the “best” engagement workflow.

It comes from whether your platform can deliver on the commitments you make in a payer contract, and whether every line of code, every data pipeline, every workflow, and every dashboard is intentionally aligned with those commitments.

Most early-stage VBC startups fail not because they lack innovation, but because they lack translation:

- Translation from actuarial KPIs → into data logic

- Translation from quality measures → into workflows

- Translation from payer priorities → into product sprints

- Translation from outcomes → into defensible metrics

The winners are the founders who build that bridge early; long before QBR season, contract true-ups, or shared-savings reconciliation.

What truly differentiates a VBC startup is not its features; it is its fidelity.

-Fidelity to definitions.

-Fidelity to denominators.

-Fidelity to attribution rules.

-Fidelity to clinical intent.

-Fidelity to payer expectations.

When your product measures outcomes the exact same way the payer measures outcomes, trust grows. And trust is the currency of value-based care.

Once a payer trusts your platform’s math, they trust your impact.

Once they trust your impact, they expand your contract.

Once they expand your contract, your company scales sustainably.

Founders who align early build a different kind of company.

They build platforms that:

- Move real cost curves

- Improve real patient outcomes

- Win real shared-savings dollars

- Earn real payer partnership

- Inspire real clinical adoption

They don’t chase KPIs, they shape them.

They don’t react to QBRs, they predict them.

They don’t build dashboards, they build evidence engines.

These are the founders shaping the next generation of VBC innovation.

Final Takeaway

In value-based care, your contract isn’t a business agreement; it’s a blueprint for your product. And when your team learns to translate payer KPIs into data, workflows, and features from Day 1, you stop being a vendor and start becoming a partner.

Because in VBC, the companies that win aren’t the ones that build the most features.

They’re the ones that build the most alignment.